By Hayley Boxall, Anthony Morgan, Isabella Voce and Maggie Coughlan

Originally published by the Australian Institute of Criminology

Family violence is one of the most prevalent crime types in Australia (State of Victoria 2016), with significant social and economic costs to the victim and the wider community (Department of Justice 2012; KPMG 2016). Developing more effective responses to family violence is a priority for all levels of government, as indicated by the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (Council of Australian Governments 2011) and various state and territory strategies. These plans have a specific focus on perpetrator intervention programs. While these programs have primarily targeted adults (particularly men who are violent towards their intimate partners), research shows that children and young people also use violence against their family members, including their parents, carers and siblings. Although the prevalence of adolescent family violence (AFV) has proven difficult to measure (Coogan 2011; Moulds et al. 2016; Walsh & Krienert 2007), studies have estimated that between seven and 13 percent of families experience AFV (Routt & Anderson 2011).

Abstract

Despite growing recognition of the prevalence of and harms associated with adolescent family violence, our knowledge of how best to respond remains underdeveloped.This paper describes the findings from the outcome evaluation of the Adolescent Family Violence Program. The results show that the program had a positive impact on young people and their families, leading to improved parenting capacity and parent–adolescent attachment. However, there was mixed evidence of its impact on the prevalence, frequency and severity of violent behaviours. The evaluation reaffirms the importance of dedicated responses for young people who use family violence, and the potentialbenefits, and limits, of community-based programs.

Meanwhile, between April 2018 and March 2019, one in 10 individuals who were reported to Victoria Police for incidents of family violence were 10–19 years old (figures include intimate partner violence; Crime Statistics Agency 2019).

Adolescent family violence can have a significant impact on affected family members (Ackard,Eisenberg & Neumark-Sztainer 2007; Day & Bazemore 2011; Edenborough et al. 2008; FitzGibbon, Elliott & Maher 2018) and the young people as well (Fitz-Gibbon, Elliott & Maher 2018;Freeman 2018). Critically, there is some evidence that AFV may contribute to the development—orescalation—of violent behaviours later in adulthood (Fitz-Gibbon,Elliott & Maher 2018; Foshee et al.2005; Noland et al. 2004; Simmons et al. 2018; Ulman & Straus 2003; Vagi et al. 2013).

Despite emerging research noting similarities between the offending and reoffending patterns of young people and adults reported for family violence (see Boxall & Morgan 2020), there are unique dimensions associated with AFV which mean that programs and interventions aimed at adult offenders may not be appropriate or effective (Moulds et al. 2019). For example, in family violence situations involving an adult, the removal of the perpetrator from the household may, in some cases,help to reduce violence. However, because the young person may be legally dependent on the victim of their abuse, removal may not be feasible or appropriate (Savvas & Jeronimus 2017).

Further, interventions that are designed to deter adult offending behaviour may not be effective with young people. Adolescence is a period of rapid brain development, meaning young people can exhibit risk taking behaviour and low impulse control (Steinberg 2005). In addition, while there is an emphasis on holding offenders accountable for their behaviour through legal sanctions and behaviour change programs (Sentencing Advisory Council 2017), contact with the criminal justice system may cause more harm than good for young people (Savvas & Jeronimus 2017).

Despite recognition that young people who use family violence require a specialised response, programs for this group are relatively uncommon (Department of Justice 2012: 74; Hong et al. 2012; No to Violence 2012; State of Victoria 2016). Better known programs that have been implemented include Non-Violent Resistance (Weinblatt & Omer 2008), Step Up (Correll 2004) and the KIND Program (Moulds et al. 2019). Although evaluation has been limited, there is evidence that some AFV programs have been effective in improving parenting and reducing self-reported and parent-reported violent behaviour (Correll 2004, Moulds et al. 2019; Weinblatt & Omer 2008). Given calls by the Royal Commission into Family Violence for the expansion of therapeutic diversion programs to reduce AFV (State of Victoria 2016), building a more robust evidence base remains vital.

Adolescent Family Violence Program

The Adolescent Family Violence Program (AFVP) is an intensive case management program that aims to:

- promote positive parent–adolescent relationships and attachment;

- promote the stability of young people who are at risk of a range of negative consequences as a result of their use of violence and other co-occurring issues;

- strengthen parenting capacity;

- strengthen the young person’s emotional wellbeing, communication and problem-solving skills; and

- increase the safety of all family members by preventing the escalation of adolescent family violence.

The program is targeted at young people and their families living in three local government areas— the City of Ballarat, the City of Greater Geelong, and Frankston. The eligibility criteria for the program are broad. To participate, young people must:

- be 12–17 years old;

- reside in one of the three program catchment areas;

- have engaged in violence towards their family members; and

- consent to participate in the program

Importantly, the AFV experienced by family members does not have to have been reported to police in order for the young person to participate.

Priority for engagement in the program is given to young people with a sole female parent or carer, Indigenous people and people with younger siblings. These priority groups were selected becauseresearch shows they are over-represented among victims of family violence (Agnew & Huguley 1989;Bobic 2002; Eckstein 2004; Gallagher 2004; Paulson, Coombs & Landsverk 1990; Walsh & Krienert 2007).

When the evaluation was conducted, the AFVP comprised two core components—intensive family case management, and voluntary group work. Intensive case management involved the young person, their parents/carers and other family members meeting at regular intervals (typically weekly) with a support worker. This support worker was responsible for identifying their risks and needs and developing action and safety plans with the young person and their family. Case managers also supported the young people to participate in different activities and referred them to alternative services as required (eg substance abuse treatment). Case management processes were underpinned by the Victorian Government’s Best Interests Case Planning Model (Department of Human Services 2012) and family violence risk assessment and safety planning principles. Case management processes were guided by a Family Action Plan that was jointly developed by service providers and family members.

Group work activities differed between the three sites, but typically involved young people and parents/carers meeting separately in small groups to discuss the violent and abusive behaviours and learn skills to reduce and mitigate its impact (eg anger management, time out strategies). Group work typically ran for six to 12 weeks depending on the site, and were informed by the Step Up model from the United States and/or the Renegotiating Angry and Guilty Emotions model originally developed in New South Wales.

Methodology

In 2014, the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) was commissioned by the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services to undertake a process and outcome evaluation of the AFVP. This paper focuses on the impact of the AFVP in the following areas: parent–adolescent relationships; stability of housing and care arrangements for young people; health and wellbeing, communication and problem-solving skills of young people; and the occurrence and escalation of AFV The evaluation of the AFVP combined both quantitative and qualitative research methods conducted during the evaluation period (August 2014 to October 2015):

- interviews with young people (n=17) and parents/carers (n=19) from 22 families;

- analysis of assessment tools administered to parents/carers (n=37) at entry into the program and

- analysis of data collected by the service providers relating to referrals to the program and thecharacteristics of young people and their families.

A primary source of data was case file information compiled and managed by AFVP case managers for 33 young people who had participated in and exited the AFVP by the end of the evaluation period.This included 24 young people whose exits were planned (regardless of whether they completed the program) and nine whose exits were not planned. Case files were predominantly handwritten or typed notes completed by case managers as a record of their interactions with the young person and their family members, as well as feedback from other service providers engaged with the family (eg counsellors and probation officers). This qualitative information was analysed by two researchers in accordance with a coding framework developed for this study. Evidence used to assess the impact of the program included:

- the case managers’ own observations (eg ‘I believe that the relationship between the young person and their parent or carer has improved’);

- changes in behaviours and attitudes recorded between interactions or over time (eg appointment 1: the young person and parent were fighting a lot; appointment 4: the young person and family member were speaking respectfully to one another);

- changes reported by the young person or family members to the case managers (or third party;eg ‘The young person said that they felt closer to their mum’); and

- discrete events (eg the young person and parent went away on a holiday together for the first time in years).

This information was used to make an overall assessment as to whether, relative to their status at program entry, the young person and their family had improved, stayed the same, or declined by program exit. This means that if the young person or family demonstrated improvement at some point during the program but then deteriorated by the exit, they would be coded as having either stayed the same or declined.

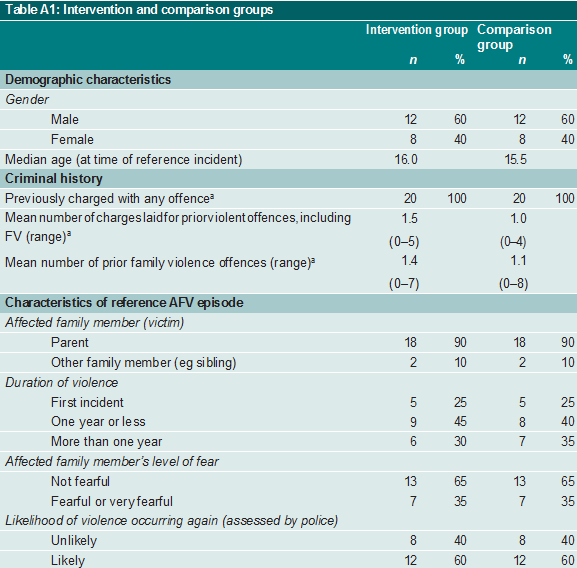

The evaluation also analysed data from Victoria Police family violence reports (L17 reports) for a sample of young people who were referred to and engaged in the AFVP by Victoria Police, who could be observed for a minimum period of 19 weeks from the date of reference L17 incident, and who consented to the AIC accessing this information (n=20, intervention group). The comparison group comprised young people aged 12–17 years old who had been identified as the offender in an L17 report completed by Victoria Police during the period 1 August 2014 to 30 June 2015 (n=3,900). Young people in the intervention and comparison groups were matched on a number of criteria (gender, age, prior charges laid, number of prior L17 reports, level of fear reported by victim,

assessed likelihood of future reoffending, and duration of violence) using a Mahalanobis distance measure (Tabachnick & Fidell 2001). Acceptable matches were found for all 20 young people in the intervention group. While the intervention and comparison groups were not matched exactly across all variables, bivariate analyses (Fisher’s exact) showed that there were no statistically significantlydifferences between the two groups (see Table A1).

Limitations

There are some important methodological limitations that need to be considered when reviewing the findings described in this paper. These include small sample sizes, the absence of post-program data and short follow-up periods. Further, while all families were invited to participate in the evaluation, young people or parents/carers who had a positive experience of the AFVP may have been more likely to agree to participate. This means that the findings from the interviews and the assessment tools may not be representative of all families participating in the program. Critically, because of these limitations, we cannot make a definitive statement or assessment as to the impact or effectiveness of the AFVP. Rather, this study is exploratory and examines whether there is evidence that the AFVP has promise as a strategy for improving the safety of families affected by AFV.

Findings

Program participants

Between August 2014 and October 2015, 237 young people were referred a total of 270 times to the AFVP. The most common source of referrals was Victoria Police (50%, n=132). Eighty-two young people consented to participate in the AFVP and the majority went on to participate in the program. By the end of the evaluation, 30 young people had completed the program (ie had a planned exit), 21 had left the program prior to completion (unplanned exit) and 31 were still participating (active clients). The mean length of engagement for young people who had exited the program was 24.9 weeks, but 29.6 weeks for those young people who completed the program.

Among those young people who engaged in the program:

- over two-thirds were male (68%, n=56), and the median age was 15 years;

- over half were from households with a single carer (54%, n=44; the majority of whom were female), a quarter (32%, n=26) were from ‘blended’ households (one biological parent/carer and one non-biological parent/carer), one in 10 were from a two-parent household (12%, n=10) and one (1%) lived with an older sibling;

- two in three lived in a household with other siblings (68%, n=52);

- one in 10 identified as Indigenous (n=9, 11%);

- four in five had witnessed domestic violence between other family members in their household (n=49, 80%; information was unavailable for 21 young people); and

- there was a high prevalence of co-occurring issues, including school absenteeism, mental health issues, substance use (drug and alcohol), and poor relationships with parents.

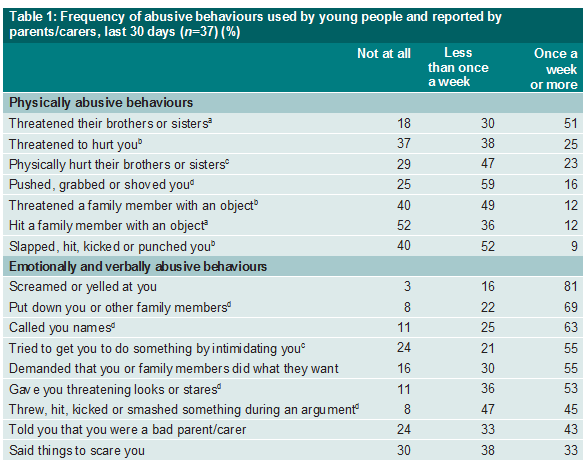

While all families were referred to the program because they were experiencing AFV, the nature and frequency of this violence varied. As shown in Table 1, parents and carers who completed the entry assessment reported a range of violent and abusive behaviours had occurred prior to and during the early stages of their involvement in the program. Verbal and emotional abuse was more common than physical violence.

a: Excludes 4 parents/carers who did not answer this question

b: Excludes 2 parents/carers who did not answer this question

c: Excludes 3 parents/carers who did not answer this question

d: Excludes 1 parent/carer who did not answer this question Source: AIC AFVP Database 2014–2015, [computer file]

Relationships between young people and parents and carers

One of the primary aims of the AFVP was to improve relationships between the young person and their parent or carer. This was achieved by improving communication between family members and providing families with opportunities for respite and to spend positive and non-violent time together (eg on outings). Several young people reported during interviews that they were getting along better with their parents or carers and their siblings as a result of the program and thought that their family was happier. Parents and carers reported similar benefits, with some saying that they were no longer

‘walking on eggshells’ around the young person and were more relaxed. One female parent/carer reflected that ‘[Young person] is still up and down with her little sister, but is more relaxed…and more patient’, while another stated that as a result of the program, ‘We are able to live together happily.’

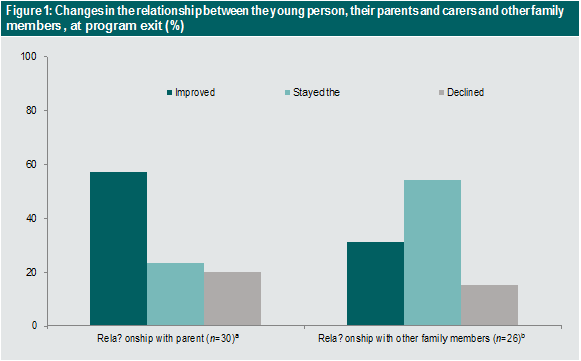

Family interviews were supported by the case file analysis, which showed that in more than half of all matters (57%, n=17), the young person’s relationship with their parents and carers had improved by program exit (Figure 1). There was no change in the relationship between young people and their parents or carers in a further seven matters (23%).

The relationship between the young person and other family members (including siblings and grandparents) improved in 31 percent of matters (n=8), while there was no observable change in 54 percent (n=14) of matters. Importantly, despite the severity of the violence and that many families were in crisis at the time of referral, relatively few young people showed signs of further deterioration in the relationship with their parents and carers (20%) and other family (15%). Some of these young people exited the program early because the severity of the issues experienced by the young person and family meant they were unsuitable for the program

a: Excludes 3 case files for which this information was missing

b: Excludes 7 case files for which this information was missing

Note: Indicators of improved relationships within the case files included the young person attending family events without incident, the young person

participating in activities with their siblings and the parents reporting that they had been spending more ‘quality time’ with the young person

Source: AIC AFVP Database 2014–2015

Stability in the lives of young people

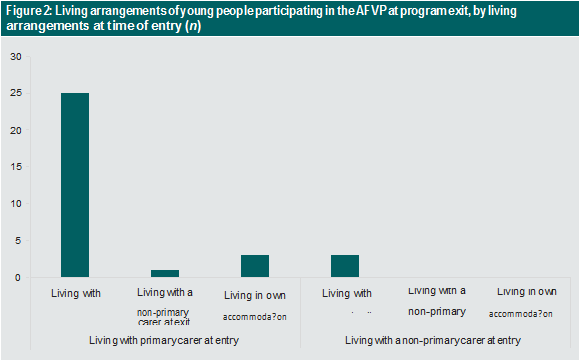

Adolescent family violence can have a significant impact on the stability of a young person’s livingarrangements. Critically, during interviews, many of the parents and carers reported that at program entry they were seriously considering or had actively sought out alternative living arrangements for the young person as a strategy for keeping themselves safe.

The analysis of the case files found that in most situations, the living arrangements of young people remained unchanged at program exit (Figure 2). Eighty-six percent of young people (n=25) who were living with their primary carer at program entry were still living with them at exit. Given the highrates of violence between parents and carers and young people, and changes to living arrangements contemplated by parents and carers at program entry, it is possible that the program prevented the escalation of violence during a period of high stress and conflict and supported families so that youngpeople could remain at home safely

The living arrangements of six young people did change. While it is unclear whether these changes were positive or negative without fully understanding the dynamics between family members, three were living with a family member at program exit. Stakeholders generally agreed that family placements were more stable than non-family placements and were preferred for this reason. The views of stakeholders are supported by a large body of research which has found that non-family placements are less stable (Rubin et al. 2008) and are associated with a range of negative experiences for young people, including disengagement from school (Pecora et al. 2006), the development/ exacerbation of mental health issues (Zlotnick, Tam & Soman 2012), and problem behaviours

(Lawrence, Carlson & Egeland 2006; Rubin, Downes & O’Reilly 2008).

Note: Excludes 1 case file for which this information was missing at exit

Source: AIC AFVP Database 2014–2015 [computer file]

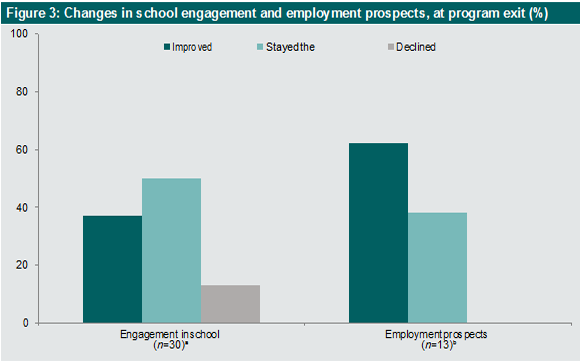

Another important focus of the AFVP was improving young people’s engagement in school and the employability of participants old enough to work. The analysis of case file data found evidence that engagement in school—reflected in increased school attendance, more positive attitudes towards school, improvement in completion of homework tasks and assessments—improved in 37 percent of cases, and remained stable in another 50 percent of cases (Figure 3). The employment prospects of young people improved in 62 percent of cases for which this was a relevant goal (ie the young person was old enough to have a job; n=8).

a: Excludes 3 case files for which this information was not available

b: Excludes 4 case files where this information was not available

Source: AIC AFVP Database 2014–2015 [computer file]

The findings from the case file analysis are supported by the family interviews. For example, one female young person reported: ‘I’m more committed to school…what I want from school and what I do at school has improved.’ One male parent/carer observed that his child was ‘attending school regularly whereas before she was wagging on a regular basis.’ Other parents and carers reported that their child had re-enrolled in school, or that the young person’s behaviour at school had improved.

Similarly, two parents reflected on the importance of their son recently obtaining a job:

We are trying to help him have better life skills. It feels like we are slowly getting somewhere… Getting himself out of bed has been a complete struggle over the last 10 years, so the fact thathe is going to work is really positive. (Male parent/carer)

Importantly, the AFVP has assisted young people and their families to access other support services.Two-thirds (70%, n=21) of all families had a new episode of contact with a support service during their involvement with the program, while three in five (61%, n=17) families were engaged with a support service at program exit.

There was less evidence that the AFVP had an impact on the health and wellbeing of young people and their families—including substance misuse and mental health. While these issues are best addressed through specialist support services, the prevalence of drinking (20% at least 2–3 times over last four weeks, as reported by young people), substance use (28%), mental illness and selfharm (16%) among young people entering the program highlights the importance of interventions to address these risk factors for violence.

Understanding and managing violent and abusive behaviour

Most of the parents and carers who were interviewed said the AFVP helped young people to understand both the drivers and impact of their violent and abusive behaviour. One female parent/ carer said, ‘I think the program has been a big learning curve for my daughter…having her own her behaviour is a huge thing for me,’ while another said her daughter had ‘an increased understanding of the behaviours and triggers…[it] feels as though she is much better equipped to handle the behaviours now’.

The program also helped parents and carers to understand the role of their parenting practices in both ‘triggering’ and de-escalating the violence and abuse (eg yelling at the young person when they did something wrong), as well as environmental stressors (eg familial breakdown, financial issues and bullying at school).

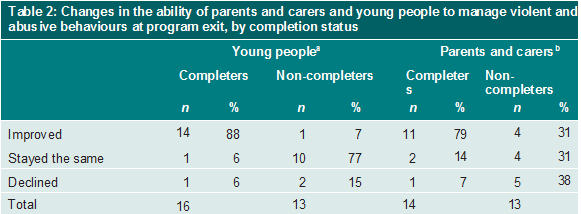

There is also evidence that the AFVP helped some families turn this increased understanding and knowledge of the young person’s behaviours into strategies. Families who participated in interviews reported that they had been able to implement strategies to prevent the young person from becoming violent, or at least to minimise the impact of violence when it did occur. This is supported by the case file analysis, which found that half of young people (52%; n=15) and parents and carers (56%; n=15) improved in their ability to manage the violence and abusive behaviour at program exit. As shown in Table 2, a larger number of families who completed the program reported an improvement in the ability of young people and parents/carers to manage the young person’s violent and aggressive behaviours, compared to families who did not complete the program.

a: Excludes 4 case files for which this information was missing

b: Excludes 6 case files for which this information was missing

Note: Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding. Indicators of improved ability to manage the violence included the young person using strategies such as ‘time

out’ to move away from potentially triggering situations and parents and carers implementing boundaries and responding to the young person’s behaviour differently

Source: AIC AFVP Database 2014–2015 [computer file]

Recurrence and escalation of violent and abusive behaviour

Taken together, the case file analysis, family interviews and analysis of surveys provided some evidence of a reduction in both the severity and frequency of violent and abusive behaviour by young people while they were participating in the program. Family interviews identified a reduction in the seriousness or frequency of violence or aggression in the home, which young people and parents and carers attributed to their involvement in the program:

At first I found it hard to stay out of fights with mum. Even though I still get angry at mum, I’mbetter at controlling it now. (Female young person)

Lots has changed already for me. My mood has been better and my behaviour has improved at home. (Male young person)

I have not had to call the police since they have been engaging with the program. There havebeen no violent outbursts and no property damage. (Female parent/carer)

Other parents and carers reported that, although the violence had declined in frequency and severity, the young person still behaved aggressively. In these situations the parents and carers said that they felt better equipped to deal with it.

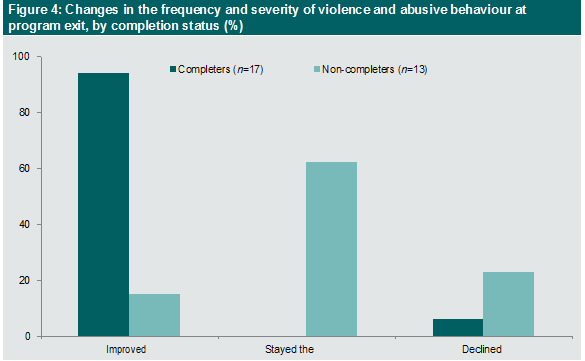

The case file analysis revealed that almost all of the families who completed the program (94%, n=16) experienced a reduction in the frequency and severity of self-reported family violence, compared with just two families who did not complete the program (Figure 4). Self-reported violence and abuse remained stable for 62 percent (n=8) of non-completers, and worsened in three cases (23%).

Note: Excludes 3 case files where this information was not available

Source: AIC AFVP Database 2014–2015 [computer file]

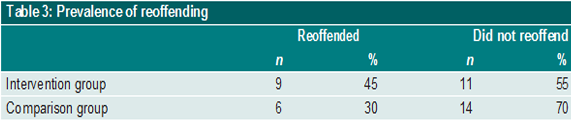

However, analysis of L17 apprehension data found no difference in the prevalence of reoffending between the intervention group (n=9, 45%) and matched comparison group (n=6, 30%) (χ2 (1)=0.96, p=0.327; Table 3). Young people who participated in the AFVP were no more or less likely to have further contact with police for a family violence matter while they were in the program than young people in the matched comparison group who were followed for an equivalent period.

Source: AIC AFVP Database 2014–2015 [computer file]

Discussion

The findings from this evaluation, and particularly the high rates of violence reported by family members, provide further evidence of the importance of a specialist, therapeutic response to AFV (State of Victoria 2016). Intergenerational family violence was common among program participants, reinforcing the need to break the cycle of violence experienced by these families (Coogan 2011; Honget al. 2012; Routt & Anderson 2011). At the same time, the many co-occurring risk factors present among young people referred to the AFVP highlight the complex task confronting service providers delivering specialist interventions to reduce AFV.

Overall, the evaluation revealed that many of the young people and their families benefited from the program in certain ways. Relationships between family members showed clear improvements. Most young people who participated in the program were living with their parents and carers at program exit. This is significant, given that many parents and carers reported that at program entry they had been exploring alternative living arrangements for their children because of the violence, and given the evidence showing the range of negative outcomes experienced by young people in foster care placements relative to family placements (Lawrence, Carlson & Egeland 2006; Pecora et al. 2006; Zlotnick, Tam & Soman 2012).

Parents and carers who participated in the AFVP also felt more confident and better able to manage their children’s behaviour, including being able to identify and respond to triggers for violent behaviour. Parenting practices that involve being overly submissive and permissive or harsh and authoritarian are well established as risk factors for both AFV (Hong et al. 2012; Pagani et al. 2004; Weinblatt & Omer 2008) and youth violence more generally (Miller, Dilorio & Dudley 2002; Schaffer, Clark & Jeglic 2008).

Service providers had some success linking families to external support services and interventions. However, there was less evidence that the program had an impact on the health and wellbeing of families, particularly the substance use and mental illness of young people.

There were reductions in self-reported emotional and physical violence, particularly among those families who completed the program. This was not reflected in the rates of offending recorded while young people were participating in the program. However, it is difficult to establish whether this is because the program did not reduce offending behaviour, or because any reductions in offending behaviour were offset by an increase in reporting by family members—a practice encouraged by the service providers. More importantly, the impact of the program beyond the intervention period remains unknown and needs to be subjected to further evaluation.

Although the current study was a largely exploratory exercise, some important lessons for future programs targeting AFV emerged. First, achieving immediate reductions in violent behaviour among high-risk adolescents requires targeting risk factors for AFV. Relatedly, given the evidence that substance use and mental illness are associated with the onset, recurrence and escalation of AFV (Calvete, Orue & Gámez-Guadix 2012; Pagani et al. 2004; Walsh & Krienert 2007), young people need integrated interventions and coordinated support to address their abusive behaviours as well as psychiatric and substance use treatment (see, for example, Crane & Easton 2017; Day et al. 2010; Savvas & Jeronimus 2017). Young people could receive multiple interventions simultaneously, or in a ‘staggered’ way. The latter option may be preferable in some circumstances. The evaluation of the AFVP identified some cases where the mental health of the young person was a significant barrier to meaningful participation in the program, occasionally resulting in young people leaving the program early to receive more intensive psychiatric support. This is consistent with the findings other research looking at adult-focused programs (Easton, Swan & Sinha 2000; Wilson, Graham & Taft 2014).

Finally, programs to reduce AFV may benefit from the inclusion of interventions that focus specifically on the young person and address their individual-level risk factors such as difficulties with cognitive processing, behavioural control and emotional management (Hawkins et al. 2000). Although case management and group work are positive and valuable interventions in and of themselves, they are primarily focused on building networks of support and addressing environmental risk factors for AFV, rather than changing the young people’s individual thought processes and behavioural patterns. This requires therapeutic treatment interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy, which rigorous research evidence has found to be effective in reducing violence, particularly among the age group targeted by the AFVP (Matjasko et al. 2012).

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to acknowledge the valuable input of Lucy Althorpe, Deanna Davy and Prue Blackmore in undertaking the evaluation of the AFVP, and the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services for funding this research.

References

URLs correct as at May 2020

Ackard D, Eisenberg M & Neumark-Sztainer D 2007. Long-term impact of adolescent dating violence on the

behavioural and psychological health of male and female youth. Journal of Pediatrics 151(5): 476–181

Agnew R & Huguley S 1989. Adolescent violence towards parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family 51(3): 699–711

Bobic N 2002. Adolescent violence towards parents: Myths and realities. Marrickville, NSW: Rosemount Youth &

Family Services

Boxall H & Morgan A 2020. Repeat domestic and family violence among young people. Trends & issues in crime

and criminal justice no. 591. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. https://aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/tandi591

Calvete E, Orue I & Gámez-Guadix M 2012. Child-to-parent violence: Emotional and behavioral predictors.

Journal of Interpersonal Violence 28(4): 755–772

Coogan D 2011. Child-to-parent violence: Challenging perspectives on family violence. Child Care in Practice:17(4): 347–358

Correll JR 2004. Long-term effects of the Step Up Program on parent participants (Master’s thesis). University of

Washington, USA.

https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/handle/1773/27501

Council of Australian Governments 2011. National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children:

Including the first three-year action plan. Canberra: Department of Social Services

Crane CA & Easton CJ 2017. Integrated treatment options for male perpetrators of intimate partner violence.

Drug and Alcohol Review 36(1): 24–33

Crime Statistics Agency (Victoria) 2019. Victoria Police July 2014 – June 2019.

Melbourne:

Crime Statistics Agency.

https://www.crimestatistics.vic.gov.au/family-violence-data-portal/download-data-tables

Day A et al. 2010. Integrated responses to domestic violence: Legally mandated intervention to programs

for male perpetrators. Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice no. 404 Canberra: Australian Institute of

Criminology.

https://aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/tandi404

Day S & Bazemore G 2011. Two generations at risk: Child welfare, institutional boundaries, and family violencein grandparent homes.

Child Welfare 90(4): 99–116

Department of Human Services (Victoria) 2012. Best interests case practice model: Summary guide. Melbourne:

Department of Human Services.

https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/publications/best-interests-case-practice-modelsummary-guide

Department of Justice (Victoria) 2012. Measuring family violence in Victoria: Victorian Family Violence Database

Volume 5: Eleven year trend analysis: 1999–2010.

Melbourne:

Department of Justice.

https://www.justice.vic.gov.au/safer-communities/protecting-children-and-families/victorian-family-violence-database-volume-5

Easton C, Swan S & Sinha R 2000. Motivation to change substance use among offenders of domestic violence.

Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 19(1): 1–5

Eckstein N 2004. Emergent issues in families experiencing adolescent-to-parent abuse. Western Journal of

Communication 68(4): 365–389

Edenborough M, Jackson D, Mannix J & Wilkes LM 2008. Living in the red zone:

The experience of child-tomother violence. Child &

Family Social Work 13(4): 464–473

Fitz-Gibbon K, Elliott K & Maher J 2018.

Investigating adolescent family violence in Victoria: Understanding

experiences and practitioner perspectives.

Melbourne: Monash University

Foshee V, Ennett S, Bauman K, Benefield T & Suchindran C 2005. The association between family violence and

adolescent dating violence onset: Does it vary by race, socioeconomic status, and family structure? Journal of

Early Adolescence 25(3): 317–344

Freeman K 2018. Domestic and family violence by juvenile offenders: Offender, victim and incident

characteristics. Bureau Brief no. 136. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

Gallagher E 2004. Parents victimised by their children. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy

25(1): 1–12

Hawkins JD et al. 2000. Predictors of youth violence. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency

Prevention

Hong JS, Kral MJ, Espelage DL & Allen-Meares P 2012. The social ecology of adolescent-initiated parent abuse:

A review of the literature. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 43(3): 431–454

KPMG 2016. The cost of violence against women and their children in Australia. Canberra: Department of Social Services.

https://www.dss.gov.au/women/publications-articles/reducing-violence/the-cost-of-violence-againstwomen-and-their-children-in-australia-may-2016

Lawrence C, Carlson E & Egeland B 2006. The impact of foster care on development. Development & Psychology

1(1): 57–76

Matjasko JL et al. 2012. A systematic meta-review of evaluations of youth violence prevention programs:

Common and divergent findings from 25 years of meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Aggression and Violent

Behaviour 17: 540–552

Miller JM, Dilorio C & Dudley W 2002. Parenting style and adolescent’s reaction to conflict: Is there a

relationship? Journal of Adolescent Health 31(6): 463–468

Moulds L, Day A, Mildred H, Miller P & Casey S 2016. Adolescent violence towards parents: The known and

unknowns. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy 37(4): 547–557

Moulds L, Mayshak R, Mildred H, Day A & Miller P 2019. Adolescent family violence towards parents: A case of

specialisation? Youth Justice 19(3): 206–221

Noland VJ et al. 2004. Is adolescent sibling violence a precursor to college dating violence? American Journal of

Health Behaviour 28(1): S13–S23

No to Violence 2012. Adolescent family violence in the home: Mapping the Australian and international service

system. Melbourne: No to Violence

Pagani L et al. 2004. Risk factor models for adolescent verbal and physical aggression toward mothers.

International Journal of Behavioral Development 28(6): 528–537

Paulson MJ, Coombs RH & Landsverk J 1990. Youth who physically assault their parents. Journal of Family

Violence 5(2): 121–133

Pecora P et al. 2006. Educational and employment outcomes of adults placed in foster care: Results from the

Northwestern Foster Care Alumni Study. Children and Youth Services 28(12): 1459–1481

Routt G & Anderson L 2011. Adolescent violence towards parents. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment &

Trauma 20(1): 1–19

Rubin DM et al. 2008. Impact of kinship care on behavioral well-being for children in out-of-home care. Archives

of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 162: 550–556

Savvas E & Jeronimus A 2017. Troubled teens: Adolescent family violence requires a unique legal and service

system response. Law Institute Journal, April: p. 43. https://fliphtml5.com/lxdj/yetu/basic

Schaffer M, Clark S & Jeglic EL 2008. The role of empathy and parenting style in the development of antisocial

behaviors. Crime & Delinquency 55(4): 586–599

Sentencing Advisory Council (Victoria) 2017. Swift, certain and fair approaches to sentencing family violence

offenders: Report.

Melbourne: Sentencing Advisory Council.

https://www.sentencingcouncil.vic.gov.au/

publications/swift-certain-and-fair-approaches-sentencing-family-violence-offenders

Simmons M, McEwan T, Purcell R & Ogloff J 2018.

Sixty years of child-to-parent abuse research: What we know

and where to go. Aggression and Violent Behavior 38: 31–52

State of Victoria 2016.

Royal Commission into Family Violence: Summary and recommendations.

Melbourne:Victorian Government. http://www.rcfv.com.au/Report-Recommendations

Steinberg L 2005. Cognitive and affect development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Science 9(2): 69–74

Tabachnick BG & Fidell LS 2001. Using multivariate statistics, 4th ed. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon

Ulman A & Straus MA 2003. Violence by children against mothers in relation to violence between parents and

corporal punishment by parents. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 34(1): 41–60

Vagi KJ et al. 2013. Beyond correlates: A review of risk and protective factors for adolescent dating violence

perpetration. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 42: 633–649

Walsh JA & Krienert JL 2007. Child–parent violence: An empirical analysis of offender, victim, and event

characteristics in a national sample of reported incidents. Journal of Family Violence 22(7): 563–574

Weinblatt U & Omer H 2008. Nonviolent resistance: A treatment for parents of children with acute behavior

problems. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 34(1): 75–92

Wilson I, Graham K & Taft A 2014. Alcohol interventions, alcohol policy and intimate partner violence:

A systematic review. BMC Public Health 14: 881.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-881

Zlotnick C, Tam T & Soman L 2012. Life course outcomes on mental and physical health: The impact of foster

care on adulthood. American Journal of Public Health 102(3): 534–540

Appendix

a: Prior to the reference L17 episode

Source: AIC AFVP Database 2014–2015 [computer file]

Hayley Boxall is a Research Manager at the Australian Institute of Criminology.

Anthony Morgan is a Research Manager at the Australian Institute of Criminology.

Isabella Voce is a Senior Research Analyst at the Australian Institute of Criminology.

Maggie Coughlan is a former Research Officer at the Australian Institute of Criminology.

General editor, Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice series: Dr Rick Brown, Deputy

Director, Australian Institute of Criminology. Note: Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice

papers are peer reviewed. For a complete list and the full text of the papers in the Trends &

issues in crime and criminal justice series, visit the AIC website at: aic.gov.au

ISSN 1836-2206 (Online)

ISBN 978 1 925304 63 3 (Online)

©Australian Institute of Criminology 2020

GPO Box 1936

Canberra ACT 2601, Australia

Tel: 02 6268 7166

Disclaimer: This research paper does not necessarily

reflect the policy position of the Australian Government